Picture it: March 2020.

Actually, don’t picture it. It sucked enough to live through it the first time. Just recall with me the broad brush strokes of a global pandemic. There was a national shutdown. The president spewed a bunch of racist garbage while being of absolutely zero practical help whatsoever. And most of us huddled in our homes trying to figure out Zoom while some of us risked our lives in hospitals and grocery stores and nursing homes and warehouses.

Even in the early days, some of the news reports (the ones that didn’t refer to the disease by a racist sobriquet) recommended wearing a mask. But the prices of the few factory-made masks still available were jacked up to unbelievable heights on Amazon (Thanks, Bezos), and the government sure wasn’t giving us any.

So if you sewed, you made fabric masks for yourself and your family. You probably also made some fabric masks for your friends. You might have even made some to give away in your community.

But if you were one of the 800 members of the Auntie Sewing Squad, you helped make over 250,000 fabric masks to donate to 200 communities around the country. You prioritized the vulnerable communities that were the most affected by COVID-19 and the most disenfranchised from the political power bases that informed community response. You saved lives, you slowed the transmission of the virus, and you engaged in a form of craftivism that points out the racist and sexist infrastructure of capitalism, as well as actively disengages some of the root causes of social injustice.

The Origins of the Auntie Sewing Squad

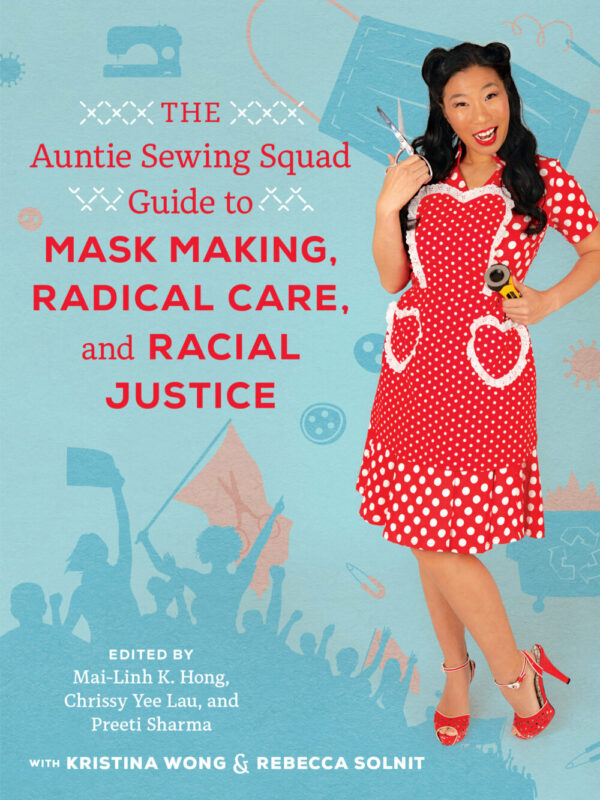

In The Auntie Sewing Squad Guide to Mask Making, Radical Care, and Racial Justice, the authors detail a history of the Auntie Sewing Squad, discuss its mission and practices, and analyze the political overtones, some overt and some subtle, of the group. In particular, the authors write about the most active months of the pandemic, and their realization that in the US, especially during the Trump reign, and most especially during a national crisis, all animals are equal, but some animals are, indeed, more equal than others:

“The Squad’s earliest members were deeply aware that the failure of the US government to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) to its residents to prevent the spread of COVID-19 had disproportionately affected Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) communities, who were more likely to contract and die from the disease. It was also clear early on that women, who perform the majority of caregiving labor in the United States (paid and unpaid), would also suffer some effects of the pandemic more than men, and that women of color would be especially vulnerable.” (The Auntie Sewing Squad 3-4)

Founder Kristina Wong organized the Auntie Sewing Squad to both donate handmade fabric masks to communities around the country and to do so in a way that overtly countered these and other deeply entrenched social injustices. The Auntie Sewing Squad prioritized, among other disenfranchised groups, workers “who were inadequately protected by the companies that employed or housed them and lacked the resources to purchase masks” (The Auntie Sewing Squad 10). They overtly chose the term “mutual aid” over “charity” to clarify that these workers and other vulnerable populations are not objects. Instead, they’re equal members of the community who are being underserved by our current social and political infrastructure. Wong even chose the group’s name to have both non-white and gendered connotations.

The Politics of Mask Making

Mask making, especially mask making in 2020, was a particularly crafty political statement because it defied much of right-wing popular media (and therefore right-wing popular opinion…) and instead was informed by the practices and experiences of those whom the right-wing media deliberately ignored: many majority-non-white nations (The Auntie Sewing Squad 5). Historically, Asian countries mask to control the spread of viruses, including past pandemics like SARS and H1N1. Many African countries also have experience with pandemics. The US could have used their advice on more than just masking… if the political leadership hadn’t been too busy lying, passing the blame, or simply ignoring the disaster. When politicians libel mask wearing, then mask wearing becomes a political act.

Here are a few of the groups that the Auntie Sewing Squad sewed for:

- asylum seekers

- Indigenous communities

- parolees

- transgender immigrants

- urban farmers

- victims of human trafficking

- low-income BIPOC communities

- Black Lives Matter protestors (The Auntie Sewing Squad 11)

These are groups that aren’t, or rather, wouldn’t need to be politicized if the political infrastructure of the US would support all individuals equally, instead of privileging a privileged few. However, by privileging these very groups as recipients of their non-capitalistic labor and handmade goods, the Auntie Sewing Squad highlighted the unjust government response to the pandemic, and directly connected it to our most long-lasting and pervasive social injustices.

And then they did something to help.